We had a brief conversation at work the other day about extending a type to make our code clearer…

public class MeaningfulName : MathsName

{

public MeaningfulName(double w, double x, double y, double z) : base(w, x, y, z)

{

}

}

We're porting some code written by our maths wizards and there's lots of convention in their domain specific language which we were trying to capture (because we're not maths wizards and (maybe only I) get easily lost).

In one case the prospective base class wasn't a class but a struct so we couldn't do this. And we briefly discussed whether we should convert it to a class.

In that conversation I stated that structs weren't value objects. You see, I've checked in the past. After a job interview where I stated that they were value objects and wrote some tests afterwards to check… I wish I still had those tests because…

Luckily, I have colleagues whose opinions I trust and I try for my opinions to be 'strong opinions weakly held' (which might be a Greg Young-ism). So while I'm having a lazy day I wrote some tests and blew my mind!

TLDR;

- Don't trust my memory

- Do test your assumptions! Do test your code! Maybe use structs!

- Clear names are likely to be much more important than C# performance.

A struct - What is it?

Value Semantics

Quoting from MSDN "A variable of a struct type directly contains the data of the struct, whereas a variable of a class type contains a reference to the data, the latter known as an object."

public class NotValueSemantics

{

public int X { get; private set; }

public NotValueSemantics(int x)

{

X = x;

}

}

var first = new NotValueSemantics(10);

var second = first;

second.X = 100;

Console.WriteLine(first.X); //writes 100

in the example above the line var second = first adds another reference to the memory that holds the first Object so operations on second affect first. The assignment of 100 to second.X is reflected in first.X.

public struct ValueSemantics

{

public int X { get; private set; }

public ValueSemantics(int x) : this()

{

X = x;

}

}

var first = new ValueSemantics(10);

var second = first;

second.X = 100;

Console.WriteLine(first.X); //writes *10*

Instead if we declare it as a struct (other than requiring a call through to the base parameterless constructor) the difference is that var second = first copies the data not a reference to it. As a result operations on second don't affect first so the assignment second.X = 100; is not reflected in first.X.

As an aside, it is possible to "break" this difference and this excellent article by Jon Skeet shows how.

Value Object

The key fact about a value object is that its properties determine what it is, so two value objects are equal when their properties are equal. Eric Evans in Domain-driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software says "you don't care which '4' you have or which 'Q'".

So here are the tests I wrote to check my understanding of structs…

[Test] //this test passes!

public void structs_with_equal_properties_are_equal()

{

var a = new ValueObject(1, 2);

var b = new ValueObject(1, 2);

Assert.AreEqual(a,b);

}

[Test] //this test passes!

public void structs_with_different_properties_are_not_equal()

{

var a = new ValueObject(1, 1);

var b = new ValueObject(1, 2);

Assert.AreNotEqual(a, b);

}

private struct ValueObject

{

public int X {get; private set;}

public int Y {get; private set;}

public ValueObject(int x, int y)

: this()

{

X = x;

Y = y;

}

}

Both of those tests pass. I'd have confidently put money on those tests failing. As above I'm certain I've written similar tests in the past and seen them fail - I should trust my memory even less than I currently do!

So a struct in C# appears to be a pretty cheap way (in terms of typing) to define a value object.

The equivalent… i.e. a class which acts as a value object.

public class ValueObject : IEquatable<ValueObject>

{

public int X { get; private set; }

public int Y { get; private set; }

public ValueObject(int x, int y)

{

X = x;

Y = y;

}

public bool Equals(ValueObject other)

{

if (ReferenceEquals(null, other)) return false;

if (ReferenceEquals(this, other)) return true;

return X == other.X && Y == other.Y;

}

public override bool Equals(object obj)

{

if (ReferenceEquals(null, obj)) return false;

if (ReferenceEquals(this, obj)) return true;

if (obj.GetType() != this.GetType()) return false;

return Equals((ValueObject) obj);

}

public override int GetHashCode()

{

unchecked

{

return (X*397) ^ Y;

}

}

public static bool operator ==(ValueObject left, ValueObject right)

{

return Equals(left, right);

}

public static bool operator !=(ValueObject left, ValueObject right)

{

return !Equals(left, right);

}

}

Much more code to read than the equivalent struct! Although I used resharper's code generation to add the equality methods so actually not that much more of the typing.

The section on differences between structs and classes on MSDN is unusually clear for MS documentation and worth a read.

So…

I've learned something and that has value. However, the team still has the problem of wanting to improve clarity. What solutions might there be.

I can think of three.

1) Don't do anything

Maybe leave it as structs and use variable names and some method & class extractiion refactorings to make what is happening clearer instead of leaning on the types to do that.

This would be fine. My feeling is that the code in question leads itself to errors because it has multiple things with the same type but different semantics being used close together. It feels like it will be easier to introduce bugs as it is - but we should always be careful so this is an option.

2) Use a wrapper class

This can be a really useful way of extending a sealed object or struct.

public class MeaningfulName

{

private MathsName _mathsThing;

public MeaningfulName(double w, double x, double y, double z )

{

_mathsThing = new MathsName(w, x, y, z)

}

public double DoAMathsThing(double a)

{

return _mathsThing.DoAMathsThing(a);

}

}

If there was a requirement to extend the functionality of MathsName and we didn't own that object then this would be a good solution but this wrapper would be calling the wrapped method with no alterations. And MathsName has a lot of methods :(

So lots of the typing to implement but even more importantly it's possible that someone can alter MathsName without realising that they need to alter MeaningfulName too so there's the potential for bugs. It's better to help people fall into the pit of success and this solution doesn't do that.

3) Change it to a class

There'd not be very much of the typing. Only the addition of the equality methods (and probably some equality tests for safety). The struct in question is relatively well covered anyway so the change would be safe.

But we create tens of thousands of these structs and pass them around. What would the impact of converting this to a class be. Class vs. Struct - the big fight ———-

I created a console application that creates a bunch of objects and structs and then calls a method on them. You can see the full program here.

public class ValueClass : IEquatable<ValueClass>

{

public double Z { get; private set; }

public double Y { get; private set; }

public double X { get; private set; }

public double W { get; private set; }

public ValueClass(double w, double x, double y, double z)

{

W = w; X = x; Y = y; Z = z;

}

public static ValueClass operator +(ValueClass left, ValueClass right)

{

return new ValueClass(left.W + right.W, left.X + right.X, left.Y + right.Y, left.Z + right.Z);

}

//snip equality members

}

public struct ValueStruct

{

public double Z { get; private set; }

public double Y { get; private set; }

public double X { get; private set; }

public double W { get; private set; }

public ValueStruct(double w, double x, double y, double z) : this()

{

W = w; X = x; Y = y; Z = z;

}

public static ValueStruct operator +(ValueStruct left, ValueStruct right)

{

return new ValueStruct(left.W + right.W, left.X + right.X, left.Y + right.Y, left.Z + right.Z);

}

}

and then doing something like

private static void AddObjectsTogether()

{

var endValues = new List<ValueClass>(Capacity);

foreach (var value in CreateABunchOfObjects())

{

endValues.Add(value + MakeRandomValueClass());

}

}

Profiling

First I profiled the application running with a Capacity of 25 million. The code spent a little less than 10% of its time dealing with the structs and a little more than 12% of its time dealing with classes. Running with a capacity of 250,000 showed the reverse.

What this told me was I don't really understand profiling… Doh!

And you can create seventy five million structs in 2.8 seconds and seventy five million object in 2.3 seconds. That's orders of magnitude higher than I care about.

Memory

When running the program to generate the structs it ran for about five seconds, preallocated around 790MB memory and kept that amount of memory in use until the end

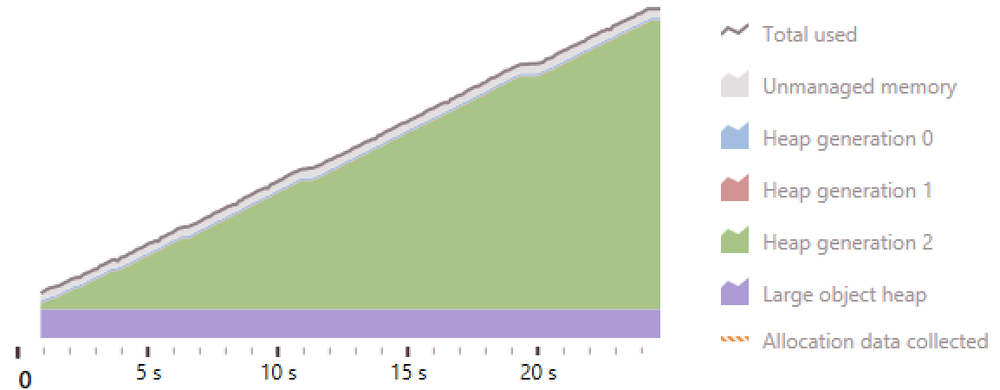

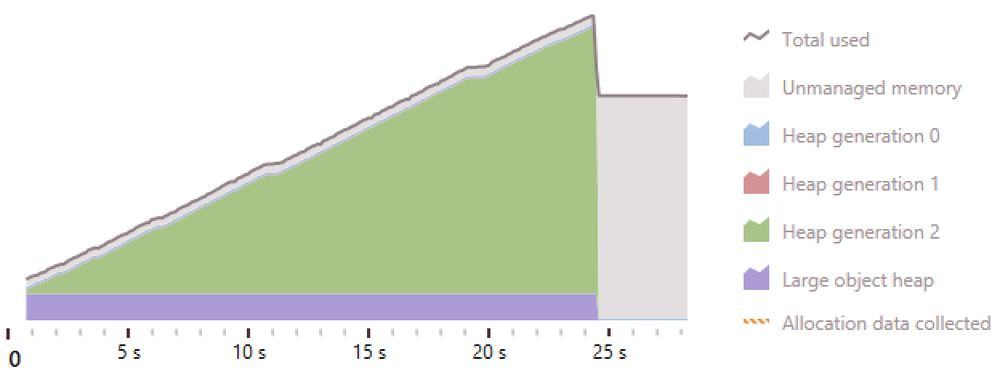

When running the program to generate objects it ran for about thirty seconds, used slightly more memory, but didn't preallocate the memory.

When running the program to generate both it ran for about thirty seconds, used slightly more memory, but didn't preallocate the memory.

What this told me was I've no idea about memory profiling… Doh!

But that there's some tradeoff to be made where if you are creating primarily structs the compiler can preallocate memory to speed things up but if you aren't then it cannot - maybe?! That needs some research…

Performance

I definitely need to learn how to profile programs.

The speed-up when dealing primarily with structs is intriguing but:

- it came with more constant memory usage - easier to budget for but possible requires more overall

- I don't think the real code that led to this is primarily structs so this might be a red herring

Overall

A much longer and more rambling post than anyone deserved to read!

Do test your assumptions! Do test your code! Maybe use structs!