At the 2019 Manchester Java Unconference I attended a discussion on "Cloud Native Functions". It turned out nobody in the group had used "cloud native" but I've been working with teams using serviceful systems.

I have a bad habit of talking more than I should but, despite my best efforts, the group expressed interest in hearing what teams at Co-op Digital had learned in the last ten months or so of working with serviceful systems in AWS.

We defined some terms, covered some pitfalls and gotchas, some successes, and most of all our key learning: that once you can deploy one serviceful system into production you can move faster than you ever have before.

Let's spend a little while defining our terms…

Cloud Native Functions

The Cloud Native Computing foundation is a group of companies seeking to define open standards for systems built to run on "the cloud".

Cloud native technologies empower organizations to build and run scalable applications in modern, dynamic environments such as public, private, and hybrid clouds. Containers, service meshes, microservices, immutable infrastructure, and declarative APIs exemplify this approach.

from: https://github.com/cncf/foundation/blob/master/charter.md

Seeking to build "a constellation of high-quality projects that orchestrate containers as part of a microservices architecture."

So, cloud native functions are (container based) systems that allow you to run functions as a service (Faas).

Function as as a Service (FaaS)

These are compute environments that let someone deploy a function that will run in response to events triggered by the environment.

AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud Platform all have a FaaS offering. There are systems like kubeless that let you run infrastructure (or rent it from someone else) and run your own FaaS environment on top of that.

CNCF has a landscape view at time of writing that has 58 serverless products on it.

If I only convince you of one thing in this post I want it to be this: none of the items in the "installable platform" section are Serverless. Doesn't mean they aren't potentially valuable to someone but…

Serverless

There's quite a bit of definition of serverless in a previous post.

Boil it down to this: there is no installation, configuration, or maintenance of servers for the owners, and builders of a service in a Serverless system.

In most cases your team (or worse a different team in your organisation) will provision, manage, patch, security scan, and deploy servers either physical or virtual. Unless you sell the compute those servers represent then you don't make money only by running those servers.

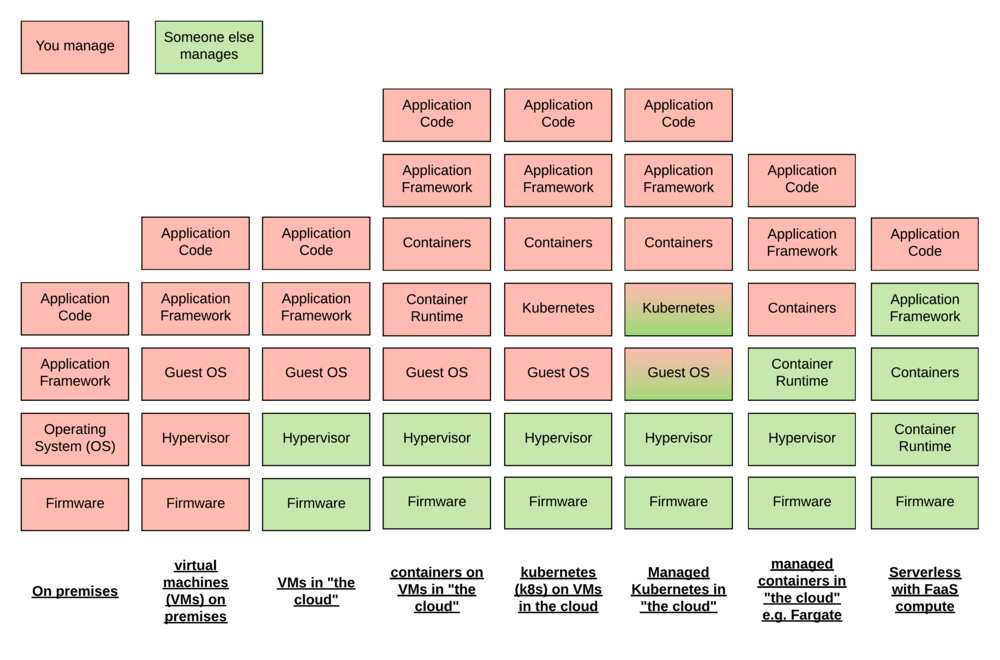

In this image we can see that adding containers or kubernetes might make your systems "Serverless" to a traditional development team, one that has no access to or responsibility for infrastructure. But it increases the amount of infrastructure to provision, patch, and scan for vulnerabilities for your organisation. It increases the amount of things to manage that don't directly add value.

It's only as you move to a system like EC2 fargate or GCP cloud run where you only bring the containers that you start to reduce the amount of infrastructure management you need to carry out.

I'm partly excluding managed kubernetes from that or at least withholding judgement. A little because I'm not familiar enough to say if it meets this definition but also partly because in Amazon EKS you are still responsible for bring the machine images that kubernetes worker nodes run on. So you're still responsible for the scanning and patching of those images.

On the right you then have what most people think of when you say Serverless which is something that should probably be called "Serverless with FaaS compute". Serverless has existed (if not named) since tools like S3 became available. FaaS allows you to more obviously include your business logic to tie together the various available serverless services.

Here you tradeoff not being able to bring your own application framework with the freedom of having an almost zero maintenance load. So long as you scan your dependencies, and perform some static or dynamic analysis of your code you can offload the responsibility for the rest of the maintenance and management of the system to the utility provider.

Serviceful Systems

Some folk don't get on with the name serverless. Myself it is because of the confusion between FaaS and Serverless making it hard for people to understand how to approach building these systems. My colleague Chris Sewart introduced me to the idea of calling it "serviceful" instead. The earliest reference for the name I can find is Patrick Debois at Serverlessconf. A 30 minute video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bYCPbKHivMA

Instead of concentrating on not having servers. Concentrate on making best use of services. The example my colleague uses is that if you want a file system you almost certainly want NFS because it's an excellent file system. But that generally speaking you don't really want a file system you only want somewhere it is easy to put files. As a result you should use S3 (if you're in AWS) because that's a really easy way to store files.

In a serviceful system you should default to consuming the service. The service doesn't come with the provisioning and maintenance burden of the not-service. Even if the not-service is in some way better it needs to be a lot better to justify its cost.

- Yes, NFS is great but use S3

- Yes, RabbitMQ is great but use SQS

- Yes, ${MVC Framework of choice} is great but use API Gateway and Lambda

- etc

- etc

Technical debt vs Accidental complexity

To aid some of the below…

Technical Debt

Most teams call an awful lot of things "technical debt". I like to restrict it to one particular thing… decisions we made on purpose to do something with a poor level of technical correctness because it let's us get to production faster. Technical debt is not a bad thing - so long as you are disciplined about replacing the bad thing with a better version once you've proven the need for it.

Accidental Complexity

A lot of teams call this "technical debt" without distinguishing it from "technical debt". Accidental complexity (defined by Brooks in 1986 in the "No Silver Bullet" paper) is complexity that we add that doesn't need to be in the system. As distinct from essential complexity that does need to be in the system.

E.g. we wrote a tax processor which handles complex tax rules… and we wrote our own queueing software to do it. The essential complexity of the tax rules might be swamped by the accidental complexity of the home grown queue.

Or we repurposed the existing Oracle analytical DB to support our website because it already handled the complex business logic. The essential business logic complexity might be outweighed by the workrarounds needed to make an analytical DB look like an online transaction processing DB.

(not that I've been burned by inheriting decisions that look like either of those two ;))

Blimey charlie that's a lot of definition of terms!

Let's see if it helps…

Background / Context for my experiences

I work with a team that build customer, member, and offers systems for the Co-op. At one point the team was 200 people from 3 different consultancies. It's now only a few more than 20.

200 people working to a short deadline even bringing their best selves every day can introduce an awful lot of technical debt and accidental complexity.

Dealing with that debt while adding to and fixing our systems was making us very slow. We chose the principle of preferring immutability and composability at every level. Choosing serviceful systems has enabled that and meant that we make most things such that they can be added alongside what already exists. That means we can work without adding to the already high maintenance burden of the serverful systems that exist.

That lets us deal with technical debt and accidental complexity at a different cadence than we deal with our sponsors' and users' needs. We already run in AWS so we chose to use AWS lambda for FaaS and DynamoDB for (sort of) key-value storage. We were already using SQS (queue), SES (email), and S3 (storage).

Event driven and asynchronous or GTFO

The first thing to accept is that this is an event-driven approach. You have to approach the design of your system as lots of little things talking to each other by raising events (albeit implicitly). If you can't or don't want to then you're not going to get on with this way of building things.

Where something is synchronous (e.g. an API call) you have to know that you can process and respond in a short enough time or that you can fake a synchronous system. For example if you can always succeed (at least after retry) then return 20x to the calling client, put their request into SQS, and move on.

In most cases you should already be thinking of your system as little, independent things talking to each other by sending messages. However, it was fascinating to have someone in the JManc discussion group that worked at Elastic on ElasticSearch. Such a different development context and you could see that things that were absolutely true for them didn't make sense for me and vice versa.

(Always important to remember that we all say "pattern" a lot and that means: a problem, a solution, and a context. Here we saw how a change of context meant a good solution in one context was a bad solution in the other)

Empowering if you empower

When I joined this team only QAs were allowed to deploy to production and only platform engineers made any infrastructure changes. It was inherited behaviour and it was debilitating for productivity. It also meant that folk with deep expertise in important tasks were snowed under with trivial tasks that didn't require their expertise. Because they were siloed the different groups sat separately and worked separately so shared very little understanding of each others needs and difficulties.

The stability, reduced complexity, and reduced attack surface of Serviceful systems has helped give us the confidence to collapse those silos. Software engineers now regularly write terraform, platform engineers and QAs join the mob, and folk sit together.

We also noticed people starting to thank each other as they got to know each other and understand the work being done. Of all the things we've achieved together this is the one I'm most proud of. So while I wouldn't argue the behaviours are unique to serviceful systems I wouldn't want to leave out the contribution they made.

Cheap and fast and slow

Cheap

Cost isn't the most important thing - developers can cost much more than infrastructure. But we've been building entirely servicefully for more than a year now and our systems do more than they used to but at worst our AWS bill has been flat over that year. We use cloudability to track our spending and that predicts a 10-20% drop in bill over the next 12 months based on change over the last year.

In fact one of our engineers has paid his salary in cost reductions on our inherited Serverful systems. That almost certainly means we've invested upwards of $200,000 since the team was launched that could have been avoided. Engineers are more expensive than infrastructure so let's guess that we invested $1.5M to create that avoidable $200k. Arguably, that's going on for $2M invested not to achieve any value at all. At best it was scaffolding that enabled the valuable work. At worst, avoidable in its entirety.

Serviceful systems were less mature back when that investment was being made so it may well have been the right investment then… but they're much more mature now. To the point that it should be your default choice. Your context might force a different choice. But my assertion is that teams should assume they're building Servicefully and discover where they can't.

S3 and dynamo are our highest serverless cost. Lambda is effectively free still despite running production workloads and underpinning the majority of our scheduled infrastructure tasks.

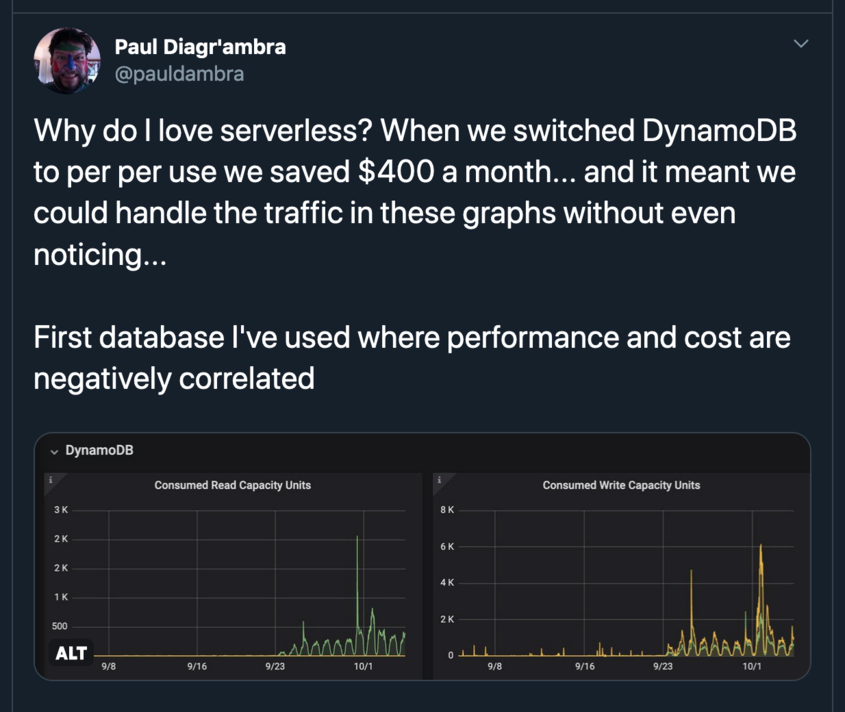

DynamoDB was rising in cost. We discovered this was because we were setting tables to fixed provisioned capacities. In order to fix a performance issue we set Dynamo to "on demand" i.e. serverless mode. Not only did that fix our performance problems but also reduced cost by about 80%. The moral of the tale here is you get forensic visibility into the cost of what you're running. But you have to make sure you're using a service like cloudability and are checking what you're spending.

You have to make sure you are looking at the cost profile of the services… AWS Cognito is cheap as chips, AWS Cognito with Advanced Security suuuuupeeerrrrrr expensive.

AWS API Gateway is super cheap and has per request pricing. While Azure API Management service you pay to reserve capacity so at much lower traffic levels (comparitively) you could end up spending more than running an API gateway yourself. You can't assume Serviceful is cheaper but when you cut with the grain there's a good chance it is.

and fast

These services are (in our experience, in AWS) rock-solid, stable, and fast. But they're also fast to build. Once you know how! The group building Offers took two weeks to get their first API Gateway > Lambda > DynamoDB system into production. They took one day to get the second out.

It's now faster for the team to create two competing designs of a thing and then measure them than to research which might perform better. As you build capability at this way of working your pace can grow much more easily.

and slow

But you are also accepting that you are leaning on a framework that you can't play around with. We use a number of existing dependencies that live inside a VPC (a private network in AWS) and so we have to deploy some lambdas inside that VPC.

At the time of our first implementations cold start of a lambda function in a VPC took a pretty consistent ten seconds. For an offline batch process that doesn't really matter but if you connect that up to an API that's abysmal.

Since that JManc discussion AWS have released a fix to that performance issue. But it's a great example of how you may have to accept the tradeoff of not being able to build exactly what you want in the way you want in order to get the benefits of the serviceful approach.

It's also a great example of why I'd recommend AWS for Serviceful/utility hosting. The speed at which they iterate and improve based on customer feedback is startling.

Commit to learning

This is a relatively new way of making systems and pushes you into less familiar approaches. If you start down this road you should make a point of introducing protected time for individual and group learning. We definitely missed a trick here and it took longer than necessary to get good at this.

You should have protected learning time anyway but especially while you introduce something so new to everyone.

One of the things that helped fantastically was the team's practice of preferring to mob on work. That's helped keep everyone moving their understanding along at the same rate.

The next steps the team needs to take are to start to formalise and describe some of what we did so that other teams can start to take advantage of it.

This is forking awesome

We're doing more, with fewer people, at greater value, and lower cost. And it's been a genuinely joyful process.

I'm more than happy to stick my flag in the ground and repeat from above that serviceful systems are more than mature enough and more than valuable enough that you should have to justify why you're not using them.