Part One - describing event-driven and serverless systems

Part Two - Infrastructure as code walking skeleton

Part Three - SAM Local and the first event producer

Part Four - Making streams of events

Part Five - Making a read model

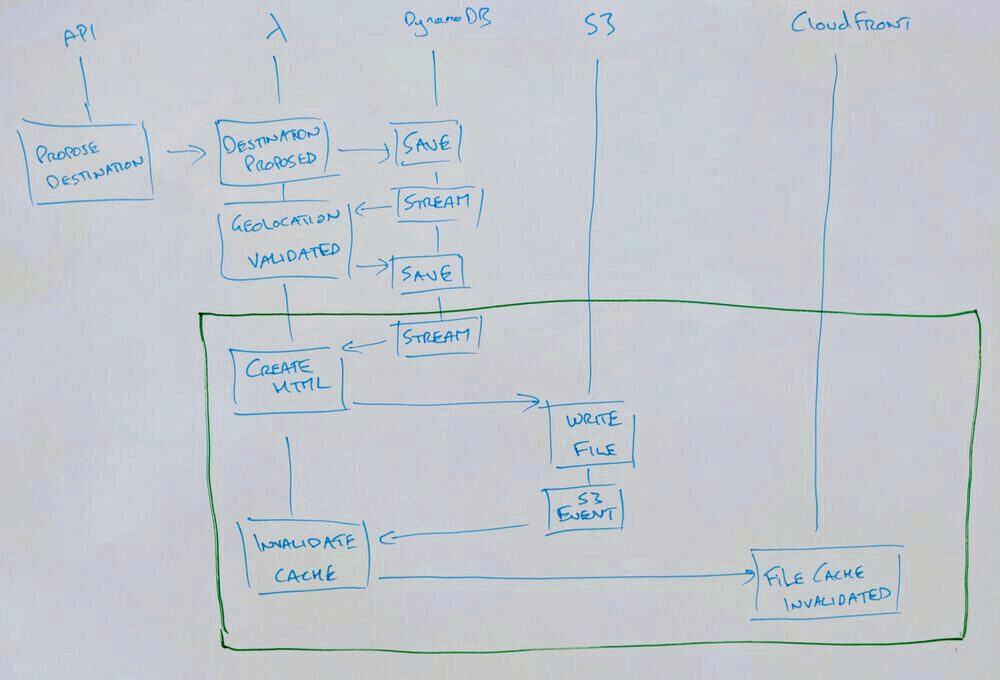

In part 5 the code was written to make sure that whenever a destination changes the recent destinations read model will update. Now that read model can be used to realise a view that a human can use. We'll add code to create a HTML view behind AWS cloudfront. This will demonstrate how event driven systems can be created by adding new code instead of changing existing code.

Where were we?

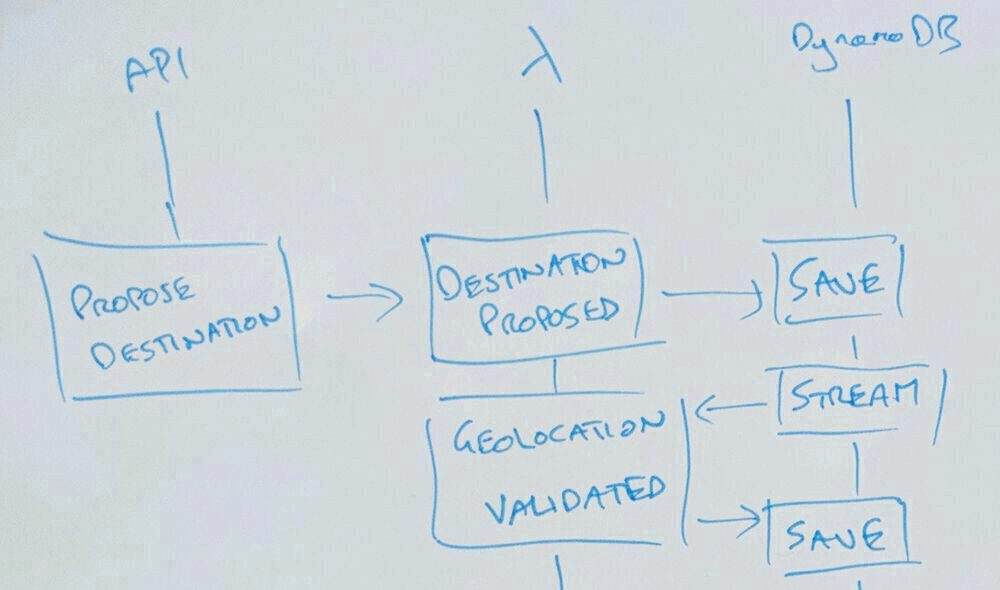

The system so far allows an API call to propose a destination someone might want to visit. When that ProposeDestination command is received after a little validation a DestinationProposed event might be saved to DynamoDB. A lambda is subscribed and when that event is raised validates the location of the destination - you can't visit somewhere that isn't anywhere after all. That lambda saves either a geolocationValidationSucceeded or geolocationValidationFailed event to DynamoDB.

Right now there are no consumers of the geolocationValidationFailed event. When one is necessary, for example to let the destination proposer know we need their help to correct the record, nothing already written has to change. A new subscriber would be added alongside.

The last change was to add a subscriber to any event in the stream. An event being received is a strong indication that a destination changed so its job was to make sure that destination is stored or updated in DynamoDB.

Most systems only save that final data and throw away all the other lovely information. Maybe they come pretty close to saving the same information because they write it as log messages. A form of event stream that is very difficult to consume.

ReadModels are Projections are ReadModels

If you're familiar with SQL then you've typed something like Select name, thing, clink, andStuff from myTable before now. That list of properties is the projection. The structural representation of the data in the store that will be the query result.

Since a read model is a representation of the data that is provided for one or more reads or queries then a read model is a projection.

Generally speaking you can say either ReadModel or Projection. Some people distinguish between ReadModel as a set of data and Projection as a stream of that data which might be a useful distinction.

Where does this change take us?

This set of changes puts the system in a position to be able to serve a HTML home page that shows the most recently changed destinations. Get the champagne on ice this start-up is heading to exit.

This change adds two new lambdas (or subscribers, or consumers).

Creating HTML

The destination stored to DynamoDB is our read model but in the beauty of an event driven system can also be subscribed to. This means we don't have to read from DynamoDB when somebody wants to put that data into HTML to display to a user.

Because the system is event driven we know whether the data has changed so we have an hook for cache invalidation. That means the system can generate HTML whenever the set of destinations changes.

The handler should look familar now:

const AWS = require("aws-sdk");

const region = process.env.AWS_REGION || "eu-west-2";

const s3 = new AWS.S3({ region });

let documentClient;

const dynamoDbClient = require("./destinations/dynamoDbClient");

const lambdaHandler = require("./destinations/homepage/handler");

const readModelsTableName =

process.env.READMODEL_TABLE || "vistplannr-readmodels";

exports.handler = async (event) => {

documentClient = documentClient || dynamoDbClient.documentClient();

const handler = lambdaHandler

.withTableName(readModelsTableName)

.withDocumentClient(documentClient)

.withStorage(s3, "visitplannr-site-home");

const promise = handler(event);

promise.catch((err) => console.log(err, "error generating homepage"));

return promise;

};

It acts as the composition root, gathers dependencies, injects the dependencies into the system, and handles the event. So the code can be tested completely decoupled from the dependencies.

The actual code is straight forward. Read something from one place, transform it, and write it to another

const guid = require("../../GUID.js");

const makeReadModelRepository = require("../destinations-read-model/make-readmodel-repository.js");

const generate = require("./htmlGenerator");

const writeToS3 = (html, s3, bucketName) => {

const params = {

ACL: "public-read",

Body: html,

Key: "index.html",

ContentType: "text/html",

Bucket: bucketName,

};

return s3.upload(params).promise();

};

module.exports = {

withTableName: (tableName) => ({

withDocumentClient: (dynamoDbClient) => ({

withStorage: (s3, bucketName) => {

const readModelRepo = makeReadModelRepository.for(

tableName,

dynamoDbClient,

guid

);

return async (event) => {

console.log(event, "triggering event");

// we don't care about the event o_O

const destinations = await readModelRepo.read(5);

console.log(

destinations,

"loaded destinations for home page generation"

);

const html = generate.homepage(destinations.Items);

return writeToS3(html, s3, bucketName);

};

},

}),

}),

};

So now whenever there's an event the HTML is templated and written to S3.

Invalidating the Content Delivery Network's Cache

The bucket that the templated HTML is written to is being served as a static site behind the CloudFront CDN. A CDN is a bunch of computers that cache a copy of your content close to the edge of the network so that it can be delivered to users as quickly as possible.

Because the HTML is behind a CDN writing to the bucket isn't enough. The CDN carries on serving the old cached content. So writing to S3 will also need to invalidate the CDN's cache.

That could be done in the same lambda as writes the event to S3 but writing to S3 is itself a lambda trigger. So we can encode the behaviour "when the static content changes invalidate the cache" instead of "when this particular reason for the content to change happens invalidate the cache".

Having a separate lambda continues to demonstrate you can take advantage of the additive nature of an event driven system.

const AWS = require("aws-sdk");

const cloudfront = new AWS.CloudFront();

const ssm = new AWS.SSM();

const fileChanged = require("./destinations/cloudfront/handler.js");

const timestamps = require("./destinations/timestamps.js");

let cloudfrontDistributionIdParam;

exports.handler = async (event) => {

cloudfrontDistributionIdParam =

cloudfrontDistributionIdParam ||

(await ssm.getParameter({ Name: process.env.PARAM_NAME }).promise());

const invalidations = await fileChanged

.withCDN(cloudfront)

.withDistribution(cloudfrontDistributionIdParam.Parameter.Value)

.withTimestampSource(timestamps)

.invalidate(event);

return Promise.all(invalidations);

};

In what should be a familiar pattern now the dependencies are gathered, curried into the actual application code, invoked, and the results passed back out to the lambda environment to signal success or failure.

The notable difference here is the introduction of a new AWS dependency: AWS SSM. Simple Systems Manager (SSM) is a wide set of services to let you manage and configure Amazon AWS systems. The piece being used is Parameter Store.

This is a service that allows you to store plain text or encrypted config. Used here to store and provide the cloudfront distribution id. Why Parameter Store is being used is covered below.

The handler then uses the timestamp and the event to make a unique(ish) id for the invalidation and shapes the correct call to CloudFront to invalidate the cache.

What made this a fast change?

Almost everything necessary already existed

- test mechanism

- event streams

- CloudFormation templates Continuing to bang the drum for why event driven systems are so productive… Almost the entire change was the functional code to read, transform, and then write. Because the system complexity has been pushed up to the architecture the individual blocks can be simple.

Both lambdas were written in an evening.

What blew up and stopped it being a fast change?

CloudFormation was not happy with what I was trying to do… In setting out the template to add the CloudFront distribution, static site bucket, policies allowing public read from the bucket, and the two lambdas I created a circular dependency.

And had no idea what to do next :(

Luckily I know how to toot! And the lovely Heitor Lessa from AWS gave me some pointers. I particularly love that he laid out part of the path without giving me the solution - I didn't have the tools to investigate myself but will do next time now.

In the CloudFormation template the cloud front distribution ID was being set as an environment variable on the lambda that would need it. But from the help provided

# This Environment block creates the circular dependency

## CF needs S3 to be created first

#### Lambda needs CF and S3 to be created first

##### S3 needs S3->Lambda permission to be created first

###### [Fails] S3->Lambda permission needs Lambda to be created first

###### --> This circles back to point 2

This seems to be an unavoidable effect of how CloudFormation works partly because I couldn't use an S3 bucket as an event source for a lambda if it wasn't defined in the same template. So I couldn't split the templates and pass data as identifiers from one to the other.

My colleagues were particularly helpful

The best solution (we could think of) was to put the ID into parameter store from the cloudformation template to break the circular dependency.

I've been avoiding abstractions like terraform or the confusingly named serverless framework while writing this series so that I understood the nuts and bolts and this was the first time I came close to regretting this decision. Always frustrating to have things broken without knowing what to do next :'(

Two standout pieces of advice I received:

- The SAM template will generate additional CloudFormation resources for you (to save you typing them). You can reference them in the template.

So in this resource description

CloudfrontFunctionPermissions:

Type: "AWS::IAM::Policy"

Properties:

PolicyName: "CloudfrontCacheInvalidation"

PolicyDocument:

Version: "2012-10-17"

Statement:

-

Effect: "Allow"

Action: "cloudfront:CreateInvalidation"

Resource: "*"

Roles:

- !Ref CloudfrontInvalidatingFunctionRole

The !Ref CloudfrontInvalidatingFunctionRole is referencing a role in the template that isn't in the template until SAM has converted it to a full CloudFormation template o_O.

I think this is confusing but it's good to know.

- You can use cfn-python-lint to lint CloudFormation templates. It gives much better output than you get elsewhere!

Cost

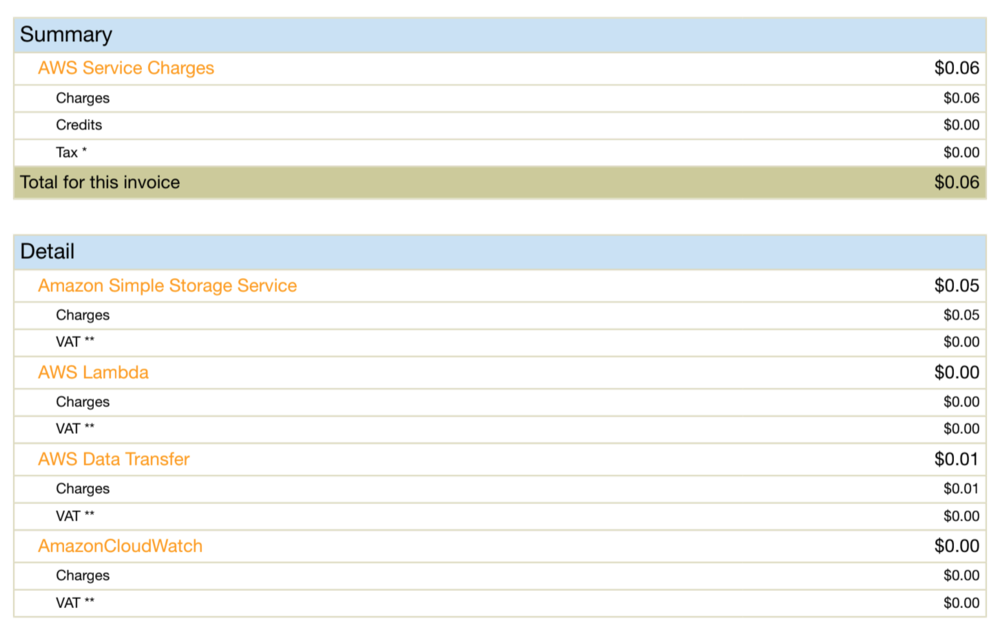

There was a lot of CloudFormation stack creation and deletion as a result of all of this. So I was very disappointed to see that it had pushed my monthly bill up gigantically.

This might seem like a silly point but creating a similarly resilient application with a serverful architecture would probably be

- 1 load balancer and 2 virtual machines for the application

- 3 virtual machines for the eventstore

- 1 load balancer and 2 virtual machines for an API gateway

(yep, and networks and security groups and and and)

That gives a monthly cost of at least $100 standing idle. I'm much happier to be stung for 6 cents.

What's the TODO list now?

We have most of the basic building blocks but only someone comfortable calling an API directly can propose a destination. The next steps from a system behaviour perspective will be to start to add a UI to propose destinations. This will start to call out the need for authentication and authorisation if it doesn't demand it outright.

From a developer's health perspective we've got quite a lot of code now. There's no bundling so the upload to S3 contains more than it needs to and it's JS - I love JS - but there're no types which can start to get confusing.

Also any system level testing is all manual at the moment which isn't good enough. There needs to be a way to visualise what is there, what it is doing, and that it works.

- visualise deployed system

- observe deployed system

- test deployed system

- bundle JS

- add Typescript

- add a propose destination form

- add auth to the system